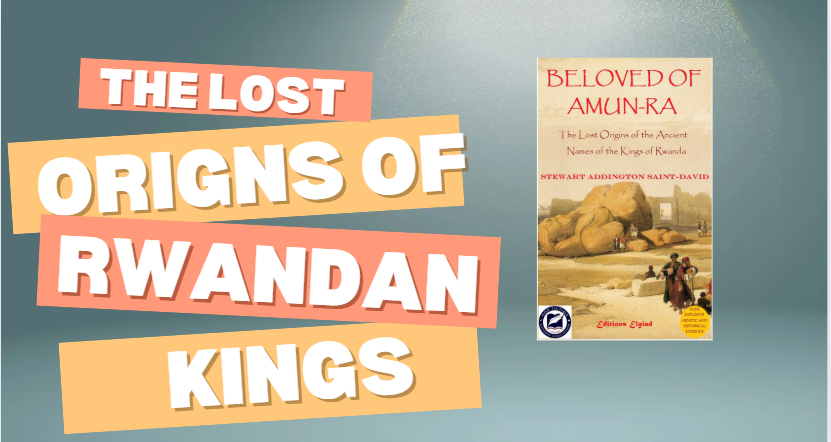

This research paper explores potential connections between ancient Egyptian and Rwandan cultures, focusing on the striking phonetic similarities between Egyptian royal names and the regnal names of Rwandan kings. The author argues that these similarities, along with genetic evidence and shared cultural practices, suggest a culturo-linguistic link between the two civilizations, possibly stemming from migrations and cultural exchange over millennia. The paper examines the meanings and origins of both Egyptian and Rwandan royal nomenclature, analyzing their linguistic components and exploring their potential shared symbolism. Finally, the paper considers the implications of this proposed connection for understanding the broader history of African civilizations and the transmission of cultural elements across vast geographical distances and time periods.

FAQ on Ancient Egypt and the Kingdom of Rwanda

- What is the central argument regarding the royal naming systems of ancient Egypt and the Kingdom of Rwanda, and what evidence supports this?

- The central argument posits a culturo-linguistic link between the regnal naming cycle of the Rwandan mwami (kings) and the royal names/epithets of pharaohs of late-period ancient Egypt. Specifically, the five recurrent Rwandan regnal names – Mutara, Kigeri, Mibambwe, Yuhi, and Cyirima – are proposed as phonetically related to the Egyptian titles “Sa-Ra,” “Kheper-Re,” “Meri-Amun-Re,” “Djehutti,” and “Iri-Ma’at,” respectively. The argument is supported by demonstrating phonetic similarities between these names, their associated functions and attributes in both cultures (e.g., Kigeri/Mibambwe as warrior kings and their association with Ra/Re), and by presenting examples of the Egyptian names within historical context. Further evidence includes the presence of five names in each system, the role of royal councilors in both cultures, and the semi-divine status attributed to both Egyptian pharaohs and Rwandan mwami.

- How did the kingdom of Kush interact with Egypt, and how might this relationship be relevant to this study?

- The Kingdom of Kush, located south of Egypt in Nubia, had a complex relationship with its northern neighbor, fluctuating between conflict and cooperation. Initially, Kush was a powerful neighbor, but Egypt later conquered and controlled the region for centuries. However, Kush later rose to power, establishing the 25th Dynasty, also known as the Nubian or “Black Pharaohs,” who ruled over both Nubia and Egypt. This period saw a fusion of Egyptian and Kushite culture, especially regarding the worship of Amun-Ra. This interaction is relevant because it highlights a period in which both Egyptian and Kushite rulers adopted similar names and titles, many of which have been associated with the later Rwandan royal names. Specifically the stele of King Harsiotef is shown using a full set of titles based on those of the Egyptian pharaohs. It also offers a pathway through which aspects of pharaonic Egyptian culture could have spread further south into central Africa through trade and population movement.

- What is the significance of the Rwandan biru in the transmission of knowledge, rituals, and royal names?

- The biru were the royal magi and ritualists of the Rwandan court. They held the esoteric codes of kingship, maintained and passed on the traditions and practices associated with the monarchy, particularly the naming and enthronement ceremonies. The biru are presented as the conduits through which Egyptian cultural elements, especially the royal names, were likely transferred into Rwandan culture. They were not only custodians of tradition, but also played a role in shaping royal names to suit their purposes, while adhering to ancient patterns.

- Why were certain Rwandan regnal names like “Nsoro” and “Ndahiro” discarded?

- The name “Nsoro” was likely discarded not for political reasons, but because the biru recognized it as redundant, being a variant of “Sa-Ra” (“Son of Ra”), which is already represented by the name Mutara within the established five-name cycle. “Ndahiro” was also eventually excluded, but has been linked phonetically to “Alexandros” (Alexander the Great), and has its root meaning of “taking an oath” associated with Alexander’s Oath of Opis. The text suggests that in reality, the exclusion may have been due to a recognition by the biru of “Nsoro’s” redundancy.

- How did the concept of cyclical time and rebirth influence Rwandan and Egyptian cultures?

- Both ancient Egyptian and Rwandan cultures shared a concept of cyclical time, where events and periods were seen as recurring. This concept deeply influenced their understanding of history, the role of the ruler, and the purpose of rituals and ceremonies. In Egypt, this was represented by the duality of djet (perfect time) and neheh (cyclical time), while in Rwanda, it was embodied in the cyclical nature of the regnal names, wherein the reign of each king was connected to the precedent established by past rulers of that same name. It led to the idea of rulers as “repeaters of births” as demonstrated by the title adopted by Seti I, “Repeater of Births”, and the proposed link to the origin of “mwami” as a possible transliteration of “wmy [msu]”.

- What specific linguistic connections are made between Egyptian and Rwandan words, and how are these explained?

The core of the linguistic argument rests on demonstrating a phonetic correspondence between certain Egyptian titles and Rwandan regnal names, allowing for some phonetic mutation and the truncation of syllables.

- Mutara is linked to “Sa-Ra” (“Son of Ra”).

- Kigeri is connected to “Kheper-Re” (“Manifestation of Ra/Re”).

- Mibambwe is associated with “Meri-Amun-Re” (“Beloved of Amun-Ra”).

- Yuhi is tied to “Djehuti” (Thoth), the Egyptian god of knowledge and communication, as well as Iah, the early Egyptian moon god.

- Cyirima is linked to “[q]Iri-Ma[at]” (“One Who Has Accomplished Ma’at [justice])

- Ruganzu is linked to the royal name Ramesses, and is argued to have shifted over time from a personal name to a regal appellation

- Mwami is argued to derive from wmy [msu], “Repeater of Births.”

These links are explained as a result of ancient linguistic transfers through oral traditions and the biru.

- Beyond names, what other cultural connections between ancient Egypt and Rwanda are explored?

- Besides the royal names, the study also notes cultural parallels including:

- The semi-divine status of the ruler. The mwami, like the pharaoh, was considered “the eye of God” or semi-divine.

- The importance of ritual and the presence of a powerful group of priests and ritualists (biru) that served to order and regulate the life of the sovereign.

- The importance of names and numbers, in both Egyptian and Rwandan culture.

- The importance of cattle, with both Egyptian and Kushite cultures linked to the rearing of cattle. The authors make note of Egyptian scribal records dating back to 2300BCE noting that the founders of some Egyptian dynasties came from the “foothills of the Mountains of the Moon” which was the home of the god Hapi, the Egyptian and Kushite god of cattle and water.

- The cyclical concept of time and rebirth.

- The symbol of the crested crane (umusambi in Kinyarwanda), the royal totem of the Nyiginya kings of Rwanda, is compared to the Bennu bird, the soul (ba) of Ra.

- The possibility of a shared genetic heritage, which has been suggested in DNA analysis of the Amarna royals.

- What are the unanswered questions, uncertainties, and future research directions suggested by the analysis?

- The study acknowledges several unanswered questions:

- How exactly these names, which were originally the product of a literate culture, came to be present in Rwanda.

- If the Rwandan regnal names were indeed originally Egyptian in origin, how they were transmitted, given the lack of widespread literacy in Rwandan society.

- Whether an as-yet-undeciphered ancient Nile Valley language, such as Meroitic, could have been a bridge through which the names were transmitted.

- The possibility of further connections between ancient Egypt and other neighboring polities like the Banyoro, Baganda, and Barundi kingdoms.

- Whether the fourfold names of the royal drums indicate another set of relationships and interconnections.

- Whether the relationship between the god Iah and fire may explain why Rwandan kings named Yuhi were considered “fire kings”.

- The study also calls for further phonetic and morphological comparisons between Rwandan and ancient Egyptian.

Quiz

- How does the Stele of King Harsiotef of Meroë connect the Kushite kingdom to ancient Egypt? The Stele connects the Kushite kingdom to ancient Egypt by portraying King Harsiotef with titles and epithets mirroring those of Egyptian pharaohs, emphasizing his devotion to Amun-Ra and his claim to rule over Nubia. It uses phrases like “Beloved of Amun-Ra” and “Lord of the Two Lands [Egypt],” highlighting cultural and religious influence from Egypt.

- What is the “five-fold royal titulary” of Egyptian pharaohs, and how is it discussed as potentially influencing the naming system of Rwandan monarchs? The “five-fold royal titulary” refers to the five distinct names or epithets associated with Egyptian pharaohs: Horus, Two Ladies, Golden Horus, Sedge and Bee, and Son of Ra names. This study guide examines how these names might have influenced the selection of the five cyclical regnal names for Rwandan kings (Mutara, Kigeri, Mibambwe, Yuhi, and Cyirima).

- According to the source, what was the significance of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt? The unification of Upper and Lower Egypt was considered a pivotal moment, marking the beginning of the pharaonic era. It consolidated power under a god-king, establishing a stable theocratic system.

- How did the kingdom of Rwanda operate politically and socially, and what roles did the Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa play? The kingdom of Rwanda was a monarchy headed by a Tutsi mwami, with a social hierarchy divided into Tutsi (aristocrats and cattle/military chiefs) and Hutu (land chiefs and agricultural laborers). The Twa were the original inhabitants, largely relegated to the margins.

- What was ubuhake, and how did it shape the relationship between the Tutsi and Hutu? Ubuhake was a patronage system where Hutu received use of Tutsi cattle in exchange for agricultural and military service. It evolved into a formalized feudal structure, centralizing power, land, and cattle ownership within the Tutsi class.

- How does the source describe the Kingdom of Kush’s relationship with ancient Egypt? The Kingdom of Kush initially flourished independently, trading and developing a unique culture, until Egypt asserted its dominance, reducing Kush to a satellite colony and absorbing Kushite forces. However, a later Kushite dynasty (the 25th) briefly controlled all of Egypt.

- What is the significance of the biru in Rwandan society, and how does the source suggest they relate to Egyptian traditions? The biru were royal ritualists who lived in the king’s palace, guided the central government and secretly determined the identity of the next king. The source suggests they might have been conduits of ancient Egyptian traditions through the naming of kings.

- What are the five regnal names of Rwandan kings, as established during the reign of Mutara I Semugeshi, and what was the associated function of the names? The five regnal names were Mutara/Cyirima (pastoral kings), Kigeri/Mibambwe (warrior kings), and Yuhi (fire kings). Each name was associated with distinct roles and attributes regarding the well-being and expansion of the kingdom.

- According to the author, how might the Rwandan regnal names connect to ancient Egyptian royal names and epithets? The author proposes that the Rwandan regnal names are phonetically similar to certain Egyptian royal names and epithets (Mutara-Sa-Ra, Kigeri-Kheper-Ra, Mibambwe-Meri-Amun-Ra, Yuhi-Djehuti, and Cyirima-Iri-Maat), suggesting a potential culturo-linguistic inheritance.

- What are some of the remaining questions the author asks about a potential connection between the royal traditions of ancient Egypt and Rwanda? The author questions how these names transferred to Rwanda 1,500 years after the end of ancient Egyptian civilization, how the people lost their literacy, whether the names were passed down orally via non-Egyptians as incantatory phrases and where, specifically, the names originated (possibly Meroitic or Proto-Northern East Sudanic) if Egyptian culture is the true source.

Answer Key

- The Stele connects the Kushite kingdom to ancient Egypt by portraying King Harsiotef with titles and epithets mirroring those of Egyptian pharaohs, emphasizing his devotion to Amun-Ra and his claim to rule over Nubia. It uses phrases like “Beloved of Amun-Ra” and “Lord of the Two Lands [Egypt],” highlighting cultural and religious influence from Egypt.

- The “five-fold royal titulary” refers to the five distinct names or epithets associated with Egyptian pharaohs: Horus, Two Ladies, Golden Horus, Sedge and Bee, and Son of Ra names. This study guide examines how these names might have influenced the selection of the five cyclical regnal names for Rwandan kings (Mutara, Kigeri, Mibambwe, Yuhi, and Cyirima).

- The unification of Upper and Lower Egypt was considered a pivotal moment, marking the beginning of the pharaonic era. It consolidated power under a god-king, establishing a stable theocratic system.

- The kingdom of Rwanda was a monarchy headed by a Tutsi mwami, with a social hierarchy divided into Tutsi (aristocrats and cattle/military chiefs) and Hutu (land chiefs and agricultural laborers). The Twa were the original inhabitants, largely relegated to the margins.

- Ubuhake was a patronage system where Hutu received use of Tutsi cattle in exchange for agricultural and military service. It evolved into a formalized feudal structure, centralizing power, land, and cattle ownership within the Tutsi class.

- The Kingdom of Kush initially flourished independently, trading and developing a unique culture, until Egypt asserted its dominance, reducing Kush to a satellite colony and absorbing Kushite forces. However, a later Kushite dynasty (the 25th) briefly controlled all of Egypt.

- The biru were royal ritualists who lived in the king’s palace, guided the central government and secretly determined the identity of the next king. The source suggests they might have been conduits of ancient Egyptian traditions through the naming of kings.

- The five regnal names were Mutara/Cyirima (pastoral kings), Kigeri/Mibambwe (warrior kings), and Yuhi (fire kings). Each name was associated with distinct roles and attributes regarding the well-being and expansion of the kingdom.

- The author proposes that the Rwandan regnal names are phonetically similar to certain Egyptian royal names and epithets (Mutara-Sa-Ra, Kigeri-Kheper-Ra, Mibambwe-Meri-Amun-Ra, Yuhi-Djehuti, and Cyirima-Iri-Maat), suggesting a potential culturo-linguistic inheritance.

- The author questions how these names transferred to Rwanda 1,500 years after the end of ancient Egyptian civilization, how the people lost their literacy, whether the names were passed down orally via non-Egyptians as incantatory phrases and where, specifically, the names originated (possibly Meroitic or Proto-Northern East Sudanic) if Egyptian culture is the true source.

Essay Questions

- Compare and contrast the political structures and theocratic systems of ancient Egypt and monarchical Rwanda, highlighting the role of the ruler, religious figures, and the concept of divine authority. How might the differences or similarities between them explain the similarities observed in the royal naming conventions?

- Discuss the significance of cattle in both ancient Egyptian and Rwandan societies, as described in the text. How did the management and ownership of cattle shape social structures and political power in these two cultures? How might this shared value explain the transference of ritual knowledge?

- Analyze the author’s argument for a culturo-linguistic link between ancient Egypt and monarchical Rwanda, focusing on the phonetic analysis of the five regnal names. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence presented, and consider alternative interpretations.

- Examine the concept of cyclical time in both ancient Egypt and Rwanda, as discussed in the text. How did these notions of time influence royal rituals, the assignment of names to kings, and overall historical consciousness?

- Explore the author’s analysis of the terms “mwami” and “wmy msu,” focusing on his hypothesis about the possible connection between the two. What conclusions can be drawn about possible transference of the term, and how does that relate to the broader argument about the ancient source of the Rwandan tradition of royal power?

Glossary of Key Terms

- Amun-Ra: A major deity in ancient Egyptian religion, formed by the combination of Amun and Ra, and regarded as the supreme god during the New Kingdom.

- Basizi: The royal chronicler-poets of the Rwandan mwami’s court, responsible for perpetuating the myths and traditions of the kingdom.

- Biru: Ritual loyalists/magi in the court of the Rwandan mwami who preserved and passed on the dynastic codes of kingship.

- Djehuti (Thoth): The Egyptian ibis-headed god of communication, history, and learning; associated with the Moon, knowledge, writing, and magic.

- Horus: An ancient Egyptian god, usually depicted as a falcon or a man with a falcon’s head, considered the god of kingship and the sky.

- Imana: The creator deity in Rwandan religion; the mwami was said to be his “eye” on earth.

- Kalinga: The drum that was a symbol of power of the Rwandan mwami, upon which the genitalia of vanquished kings were hung.

- Kush: The name given by ancient Egyptians to the kingdom that arose to their south, centered in the Upper Nile Valley (modern Sudan) and later ruled over Egypt.

- Ma’at: The ancient Egyptian concept of truth, justice, harmony, and cosmic order, essential to maintain balance in the universe.

- Meroë: A city along the Nile and a royal capital of the Kingdom of Kush during its later period, following Napata.

- Mwami: The Bantu term for king or sovereign, used particularly in Rwanda.

- Napata: An ancient city in Sudan and a royal capital of the Kingdom of Kush, before Meroe.

- Neheh: One of two aspects of time in ancient Egyptian thought, representing the imperfective or cyclical aspect of existence, the incessant recurrence of cycles of days, months, years.

- Nyiginya: The Tutsi royal clan of Rwanda, founded by Kigwa after he fell from the heavens.

- Ra/Re: The ancient Egyptian solar deity, the god of the sun, light, and creation; the most prominent god of the Old and Middle Kingdoms.

- Ubuhake: A patronage system in Rwanda in which Hutu received use of Tutsi cattle in exchange for agricultural and military service.

- Ubwiru: The complex and sacred series of rituals and practices used by the biru, guided by the reigning sovereign.

- wmy msu: An ancient Egyptian title of kings, translated as “Repeater of Births;” associated with renewal and continuity of the line of kings.

0 responses on "From Pharaohs to Bami: Exploring the Surprising Links Between Egypt and Rwanda"